The Other Slow-Cooker: The Ultimate Guide to Sous Vide Chicken

Sous vide is a method of cooking that went from science labs to Michelin-star restaurants, and has recently started showing up in the kitchens of your foodie friends. Even a few years ago, it was fairly unknown because sous vide circulators were appliances the size of aquariums and cost several thousand dollars. Recently, a number of different home immersion circulators have hit the market, so it’s possible to get a decent system for under $200, which is about what you’d pay for any kitchen appliance, and once you get started with it, this one won’t collect dust in the cupboard.

“Sous vide” is French for “under vacuum” and in practice, it typically involves a piece of meat or vegetable vacuum-sealed in a bag with some kind of seasoning or aromatic and cooked in a water bath at the desired final temperature of the food.

It might sound odd at first, and to some it conjures up memories of 80s boil-in-a-bag meals, but this couldn’t be further from that. Think for a second how traditional cooking works. We take a piece of food, and put it into an extremely hot pan or oven, and the goal is to take it out after it’s cooked, but before it OVERcooks. It’s like trying to jump onto a moving train, only not quite as cool.

On top of that, consider that food cooks from the outside in, so even for the most skilled cooks, the best case scenario is that you minimize the amount of overcooked on the outside to achieve the desired amount of cooked on the inside.

Now let’s consider how sous vide cooking works. Rather than cooking in extreme heat and pulling the chute before it burns, we cook at the temperature we want the food to hit – for theoretically as long as we like, making it virtually impossible to under or over cook your food.

If you were skeptical about this being another trendy, hoity-toity cooking fad, let this change your mind. By practically removing the upper constraint of time, creating a meal just got an order of magnitude easier. The meat’s done, but the potatoes still need another 30 minutes? No big deal. It will be fine to hang out until you’re ready.

If you haven’t quite wrapped your mind around it, think about it this way. There are two easy ways to cool a bottle of soda – in the fridge and in the freezer. If you choose the freezer, it will chill faster, but risks exploding if it freezes. The fridge on the other hand, will keep that soda cold until you’re ready for it, because it can only cool the soda to its internal temperature. Same thing with sous vide cooking – you can’t raise the temperature of something past the temperature at which you’re cooking it.

The reason we don’t cook everything at a super low temperature now is all about moisture loss. At around 170ºF, your oven becomes a dehydrator. Great for making jerky, bad for making dinner. That vacuum seal separating your food from its cooking environment also prevents the natural moisture of your food from escaping into the aether. The heat may still force some liquid from the cells of your meat, but it keeps it right next to it and adds to its flavour. Not only that, but adding spices, herbs, aromatics or fat to the bag will infuse your dinner with whatever goodness you want to add.

Now, sous vide cooking isn’t perfect, because the one thing that those searing hot temperatures are good for is… searing. Searing a piece of meat creates the Maillard reaction, which is what makes the skin brown and frankly makes it taste so good. Sous vide can’t do that, so you still need to “finish” your meat, either in a pan, on the barbecue, or with a blowtorch if you know how to party. But, since the meat is fully cooked, getting that delicious caramelized skin is really quick, so it can be done just before serving.

How It Works

To cook anything sous vide, you need three basic things. A vessel of some kind, like a large pot or heavy-duty plastic container to hold the water, a circulator, which heats the water bath evenly and constantly to an exact temperature, and a method of sealing bags.

Since sous vide cooking has taken off, there have been a number of home circulators that are in the $150 – $250 range. Some are wifi-connected and some are made to be run for 80 hours a week, but the only thing that matters is that they maintain a temperature, and that they’re calibrated correctly. A temperature reading too high or too low could result in overcooked food or possible food safety issues.

The biggest variable most people are faced with in sous vide cooking is the bag, because there’s a huge range of options with a corresponding price range. The really expensive chamber sealers are great because they can seal in liquids easily. The home food sealers that you’ll find at most hardware stores do a good job of sealing in the food, but you have to experiment with how you seal in any kind of marinade or sauce.

The good news is you don’t have to spend any money to get a good seal, thanks to our good friend Archimedes. If you remember your grade 10 science class, Archimedes got in a tub and yelled “Eureka!” But the salient point from this bath time discovery is that water can displace air through the force of buoyancy. That means that if you put a piece of chicken in a zip-top bag, and slowly submerge the bag until the water is at the top, and then seal it, you’ll have a fairly decent seal. Not quite what you’d get in a chamber vacuum, but more than enough to cook with minimal air in the bag. This is called the water displacement method of sealing.

Sous Vide Chicken

So by now, you’re obviously completely sold on sous vide cooking, so here’s what it means for your chicken dinner. Chicken is one of the best candidates for sous vide cooking because of the recommended cooking temperature of 165ºF. There’s such a small window of error between undercooked and overcooked, especially with chicken breast. With sous vide, not only can we cook with surgical precision, we can also increase the window.

Here’s where we blow your mind.

You probably know by now that the recommended cooking temperature for a cut of chicken is 165ºF. Despite the fact that Canadian farming practices result in the chicken sold in grocery stores being extremely safe, it’s still important to cook to that temperature to ensure that any bacteria that might be on or in the meat is killed. Cooking to 165ºF kills that bacteria in a matter of seconds.

Chicken cooked to 165ºF for a long time (while you wait for those potatoes) will start to break down the collagen that holds the muscle fibres together, and results in a stringy, unpleasant texture. That’s why the optimal temperature for cooking chicken sous vide is 145ºF for at least 1 hour.

Now before you start thinking “that can’t be safe!” let’s talk about why this is actually perfectly safe. Killing bacteria is a function of heat and time. At 165ºF, the bacteria is dead in 3 seconds. At 145ºF, it takes about 10 – 15 minutes. This is the same principle used in pasteurizing milk, since boiling would destroy the product. Essentially, while you’re normally dropping a nuclear bomb on the bacteria, in sous vide cooking you’re punching them to death. Less collateral damage, and either way, they won’t be around to tell the tale.

Texture

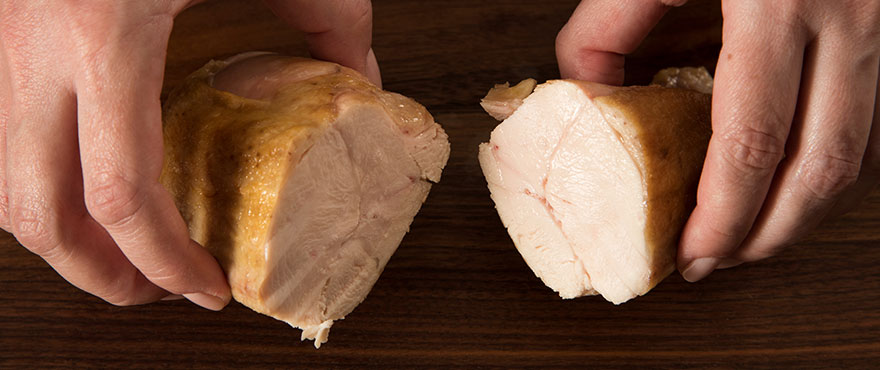

Now you’ve cooked your chicken breast at 145ºF for at least an hour and fifteen minutes. The first thing you’ll notice is that the texture is a bit different than you’re used to. The meat will be a bit softer, and light years juicier. The more you play with the temperature, the more you’ll be able to dial in the texture you like best. We find that below 145ºF is a little too soft, and that anything above 150ºF starts to feel stringy.

Finishing

When you take your meat out of the sous vide bag, it won’t quite look like food yet. A good amount of the pinkness will be gone, but because it’s cooked edge-to-edge to the same temperature, it won’t have the nice crust you’re used to, and will probably look a little pale and unappetizing. Worry not!

The easiest remedy is to heat a pan until it’s screaming hot, and dry off the surface of the chicken with a paper towel. Hit the chicken with a little salt and pepper or a rub of your choice, add some oil to the pan and place the chicken in the pan “presentation side” up. Let it cook for about 30 seconds per side, being sure to let the sides get nice and golden brown as well. You’ll know you’re done when it’s an even golden brown all the way around. Just remember that you’ve already cooked the inside of the chicken, so resist the urge to leave it in long enough for it to overcook on the inside.

This method applies to any cut of chicken, skin on or off. The only one we don’t really recommend is trying to do a whole chicken sous vide. It’s possible, but not really worth it in this method. You’re better off carving the chicken first, and individually sealing the pieces.

Safety

Sous vide cooking is safe and has been studied in labs and used in top restaurants since the 70s. That said, there are always things can potentially go wrong, and we want to avoid that. The good news is; the mistakes are easy to avoid.

First though, a quick note on plastic. Some people are understandably wary about cooking in plastic, given that some plastics can break down at high heats into chemicals you definitely don’t want to eat. That said, the typical vacuum bags that you’d use at home are designed to withstand heats far above the relatively low temperatures required for sous vide cooking. Even the typical zip-top freezer bags are BPA free now and hold up to sous vide temperatures admirably.

The biggest problem with sous vide cooking is a pesky property of physics called buoyancy. If you have a good vacuum sealer, you’re pretty much covered, but if you’re relying on ol’ Archimedes to seal your bags, you have just become a soldier in the war on floating.

If your bag is mostly sealed, it will probably look perfect at room temperature. However, as the remaining air in the bag increases in size when it’s heated, your dinner could easily turn into a personal floatation device. The problem here is that if a portion of the bag is outside of the water, it’s not being pasteurized, and that air-filled corner can become a breeding ground for bacteria. When you take it out of the water, the bacteria can run free and potentially make you sick.

Depending on the size of your cooking vessel, there are a number of clips and weights you can jerry-rig to avoid floating, but our preferred method is placing a heavy butter knife in the bag along with the chicken. That weighs it down, and will fight the upward force of buoyancy with our old friend gravity. Thanks, science!

Batch Cooking

We understand if you’re still skeptical, since you can’t taste anything we’ve written here. But the surprising thing to a lot of people who invest in an immersion circulator is how utterly practical they are on a day-to-day basis. Not only does it make individual meal prep so much easier, it makes batch cooking a breeze.

It’s not only easier, it’s cleaner and easier to batch cook sous vide for a lot of reasons. First, you don’t have to batch cook the same thing. Make lemon chicken in one bag and curry chicken in another, and the two need never meet.

Second, to borrow a phrase, you can “set it and forget it” in a way that no other method allows. As long as your chicken stays submerged in your water bath, everything is fine. You wouldn’t want to leave a chicken breast cooking all day, but you can certainly go watch a movie and come back when it’s done.

Third, there’s no packaging, since you’re cooking in the packaging. Portion out your meals in their individual cooking bags, and then can go straight from the circulator to an ice bath and into the fridge.

Finally, sous vide chicken is dead easy to reheat. It’s the same as finishing them – just throw them in a pan until they have a crust and are warmed through. Again, the chicken is cooked, so internal temperature isn’t crucial to food safety, but you’ll probably want to check the internal temperature just to make sure it’s not too cold. Anywhere from 125ºF and up is fine, but you don’t want to overcook it and go past 145ºF. If you have sides to make, you can easily reheat chicken in your circulator, and finish it quickly once it’s warmed up.

You can pre-cook chicken in whole pieces, or cut up and in a sauce. Sear it and cut it into cubes for any easy way to add protein to your work lunch, or for an easy 15-minute dinner when you get home.

TL:DR

If you’re more interested in the practical application of cooking chicken breasts than the explanation of how it works, this section is for you. Though there are many ways to make a sous vide rig on the stove or with a cooler, time and temperature are very important to food safety, so this step-by-step assumes you have an immersion circulator.

Step 1

Take the cut of chicken you like (boneless tends to work a bit better, but bone-in is fine, too), season it with salt and pepper or a rub and place it in the bag. If you’re using a sauce or a marinade, place it in the bag with the chicken.

Step 2

If using a bag sealer, vacuum seal the bag so that as little air as possible remains. If you’re using a zip-top freezer bag, remove as much of the air as you can, and then slowly lower it into a large vessel full of water. The pressure from the water will move the air up and out of the bag. Once the seal line is below the surface of the water, close it up. It won’t be a perfect vacuum, but it will do the job.

Step 3

Heat the water bath to the required temperature (~145ºF) and place the bagged chicken in the water, making sure that it is entirely submerged. Air pockets may heat up in the first 10 minutes of cooking, so be sure to keep an eye on it, and weigh down the package if it starts to float. Allow the chicken to cook for at least 75 minutes, but not more than 3 hours. The longer the meat is cooked, the more the connective tissue breaks down, which can lead to a mushy texture in lean meats like chicken.

Step 4

Once the chicken is cooked, remove it from the water bath and either place it in an ice bath to cool it down or move the chicken quickly to a pre-heated pan coated with cooking oil. Pat the chicken dry with a paper towel to allow it to sear properly. If you plan to use the cooking liquid from the bag (don’t worry, it’s pasteurized too) be sure to sear the chicken first, then add the sauce.

Remember, you don’t need to overcook the chicken in the pan – this step is simply for creating the right texture at the surface, and building up the flavour. Cooking for more than a few minutes will lead to overcooked chicken, and your last 90 minutes will be for naught.